What Percentage of Children Actually End Up Pursuing Sthe Performing Arts in Arkansas

:focal(2416x1089:2417x1090)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/96/42964a6d-02b7-465e-a4f5-6a650bbc83fb/sep2016_c02_migration.jpg)

In 1963, the American mathematician Edward Lorenz, taking a measure of the earth's atmosphere in a laboratory that would seem far removed from the social upheavals of the time, set forth the theory that a single "flap of a sea dupe's wings" could redirect the path of a tornado on another continent, that it could, in fact, be "enough to change the grade of the weather condition forever," and that, though the theory was then new and untested, "the virtually recent evidence would seem to favor the bounding main gulls."

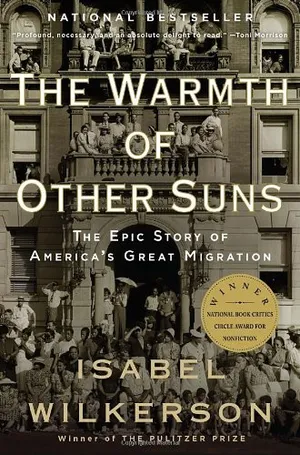

At that moment in American history, the country had reached a turning point in a fight for racial justice that had been edifice for decades. This was the year of the killing of Medgar Evers in Mississippi, of the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church building in Birmingham, of Gov. George Wallace blocking black students at the schoolhouse door of the University of Alabama, the year of the March on Washington, of Martin Luther King Jr.'southward "I Have a Dream" speech and his "Letter From a Birmingham Jail." Past then, millions of African-Americans had already testified with their bodies to the repression they had endured in the Jim Crow South past defecting to the North and West in what came to be known as the Great Migration. They were fleeing a world where they were restricted to the about menial of jobs, underpaid if paid at all, and frequently barred from voting. Between 1880 and 1950, an African-American was lynched more than once a calendar week for some perceived alienation of the racial hierarchy.

"They left as though they were fleeing some expletive," wrote the scholar Emmett J. Scott, an observer of the early years of the migration. "They were willing to make about any sacrifice to obtain a railroad ticket and they left with the intention of staying."

The migration began, like the flap of a sea gull's wings, equally a rivulet of black families escaping Selma, Alabama, in the winter of 1916. Their quiet departure was scarcely noticed except for a single paragraph in the Chicago Defender, to whom they confided that "the treatment doesn't warrant staying." The rivulet would become rapids, which grew into a flood of six million people journeying out of the South over the form of six decades. They were seeking political aviary within the borders of their own country, not different refugees in other parts of the earth fleeing famine, war and pestilence.

Until that moment and from the fourth dimension of their arrival on these shores, the vast majority of African-Americans had been bars to the South, at the bottom of a feudal social order, at the mercy of slaveholders and their descendants and often-violent vigilantes. The Smashing Migration was the outset big stride that the nation's retainer class e'er took without asking.

"Oftentimes, but to go abroad is one of the most aggressive things that some other person can practice," wrote John Dollard, an anthropologist studying the racial degree system of the South in the 1930s, "and if the means of expressing discontent are limited, as in this case, it is one of the few ways in which force per unit area can be put on."

The refugees could not know what was in store for them and for their descendants at their destinations or what event their exodus would take on the country. Simply by their actions, they would reshape the social and political geography of every city they fled to. When the migration began, 90 percent of all African-Americans were living in the Due south. By the time it was over, in the 1970s, 47 per centum of all African-Americans were living in the North and West. A rural people had get urban, and a Southern people had spread themselves all over the nation.

Merely past leaving, African-Americans would go to participate in republic and, by their presence, force the N to pay attention to the injustices in the South and the increasingly organized fight against those injustices. By leaving, they would change the course of their lives and those of their children. They would become Richard Wright the novelist instead of Richard Wright the sharecropper. They would become John Coltrane, jazz musician instead of tailor; Bill Russell, NBA pioneer instead of paper mill worker; Zora Neale Hurston, beloved folklorist instead of maidservant. The children of the Nifty Migration would reshape professions that, had their families not left, may never have been open to them, from sports and music to literature and fine art: Miles Davis, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison, August Wilson, Jacob Lawrence, Diana Ross, Tupac Shakur, Prince, Michael Jackson, Shonda Rhimes, Venus and Serena Williams and countless others. The people who migrated would become the forebears of most African-Americans born in the North and W.

The Dandy Migration would expose the racial divisions and disparities that in many means continue to plague the nation and dominate headlines today, from law killings of unarmed African-Americans to mass incarceration to widely documented biases in employment, housing, health care and education. Indeed, ii of the most tragically recognizable descendants of the Great Migration are Emmett Till, a 14-year-sometime Chicago male child killed in Mississippi in 1955, and Tamir Rice, a 12-year-former Cleveland boy shot to death by police in 2014 in the metropolis where his ancestors had fled. Their fates are a reminder that the perils the people sought to escape were not confined to the South, nor to the past.

The history of African-Americans is often distilled into 2 epochs: the 246 years of enslavement ending later on the close of the Civil War, and the dramatic era of protest during the civil rights movement. Yet the Civil War-to-civil rights axis tempts united states to jump past a century of resistance against subjugation, and to miss the human story of ordinary people, their hopes lifted by Emancipation, dashed at the end of Reconstruction, crushed further past Jim Crow, merely to exist finally, at long last, revived when they constitute the courage within themselves to break free.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/9a/359a8ce6-6c1b-46d1-90c6-51d206d91295/sep2016_c06_migration.jpg)

**********

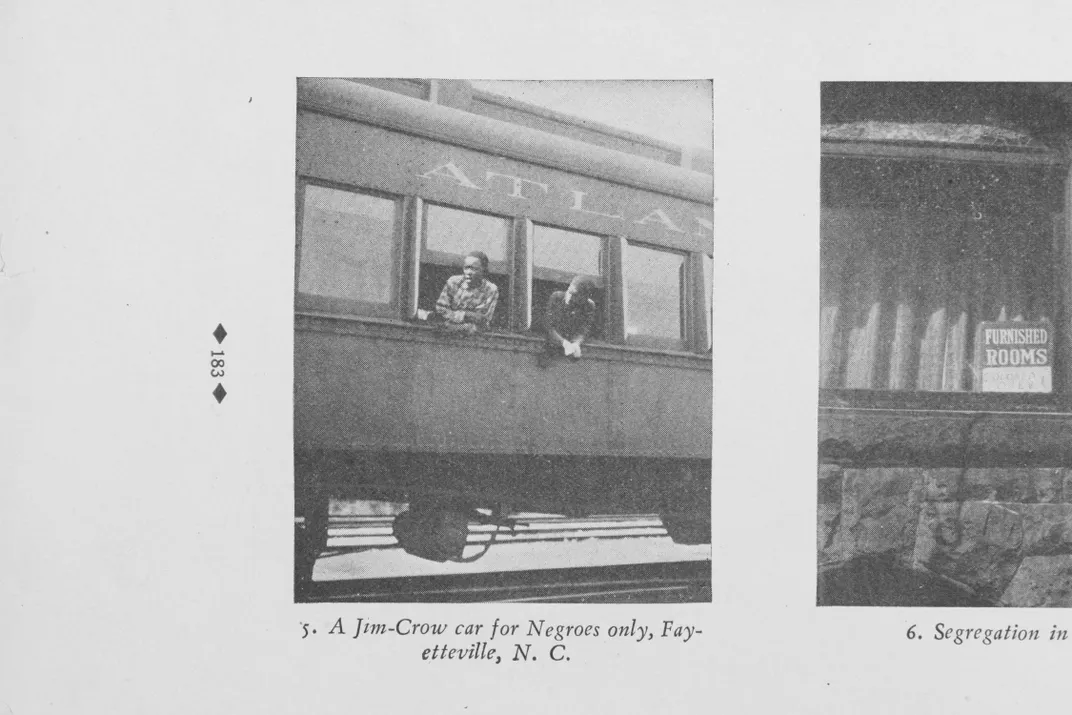

A little boy boarded a northbound train with his grandmother and extended family, forth with their upright piano and the rest of their worldly possessions, blimp inside wooden crates, to begin their journeying out of Mississippi. Information technology was 1935. They were packed into the Jim Crow car, which, by custom, was at the front of the railroad train, the showtime to absorb the impact in the effect of a collision. They would not be permitted into the dining car, so they carried fried craven and boiled eggs to tide them over for the journey.

The little boy was iv years erstwhile and anxious. He'd overheard the grown-ups talking about leaving their farm in Arkabutla, to start over upward northward. He heard them say they might leave him with his father's people, whom he didn't know. In the end they took him along. The near abandonment haunted him. He missed his mother, who would non be joining them on this journey; she was away trying to make a stable life for herself after the breakup with his father. He did non know when he would see her again.

His grandfather had preceded them north. He was a hardworking, serious man who kept the indignities he suffered under Jim Crow to himself. In Mississippi, he had not dared stand upward to some white children who bankrupt the family'due south wagon. He told the little boy that every bit blackness people, they had no say in that globe. "There were things they could do that we couldn't," the male child would say of the white children when he was a grown man with grey hair and a son of his ain.

The grandfather was then determined to become his family out of the Southward that he bought a plot of land sight unseen in a place chosen Michigan. On the trip due north, the fiddling boy and his cousins and uncles and aunts (who were children themselves) did not quite know what Michigan was, so they fabricated a ditty out of it and sang it every bit they waited for the railroad train. "Meatskin! Meatskin! We're going to Meatskin!"

They landed on freer soil, but between the fears of abandonment and the trauma of being uprooted from his mother, the lilliputian boy arrived with a stutter. He began to speak less and less. At Dominicus schoolhouse, the children bellowed with laughter whenever he tried. So instead, he talked to the hogs and cows and chickens on the farm, who, he said years later, "don't care how you lot sound."

The lilliputian boy went mute for eight years. He wrote down the answers to questions he was asked, fearing even to introduce himself to strangers, until a high school English teacher coaxed him out of his silence by having him read poesy aloud to the class. That male child was James Earl Jones. He would proceed to the University of Michigan, where he abandoned pre-med for theater. Later he would play King Lear in Central Park and Othello on Broadway, win Tony Awards for his performances inFences and inThe Great White Hope and star in films similarDr. Foreigndear,Roots,Field of Dreams andComing to America.

The voice that fell silent for so long would become among the most iconic of our time—the vox of Darth Vader inStar Wars, of Mufasa inThe Lion King, the vocalism of CNN. Jones lost his vox, and constitute it, because of the Not bad Migration. "Information technology was responsible for all that I am grateful for in my life," he told me in a recent interview in New York. "We were reaching for our gold mines, our liberty."

**********

The desire to exist free is, of class, homo and universal. In America, enslaved people had tried to escape through the Underground Railroad. Later, one time freed on paper, thousands more, known every bit Exodusters, fled the violent white backfire following Reconstruction in a short-lived migration to Kansas in 1879.

Merely concentrated in the South every bit they were, held captive by the virtual slavery of sharecropping and debt peonage and isolated from the residual of the country in the era earlier airlines and interstates, many African-Americans had no set means of making a go of it in what were and so faraway alien lands.

By the opening of the 20th century, the optimism of the Reconstruction era had long turned into the terror of Jim Crow. In 1902, ane black woman in Alabama seemed to speak for the agitated hearts that would ultimately propel the coming migration: "In our homes, in our churches, wherever two or iii are gathered together," she said, "there is a discussion of what is best to exercise. Must we remain in the South or get elsewhere? Where tin nosotros go to feel that security which other people experience? Is it all-time to go in great numbers or only in several families? These and many other things are discussed over and over."

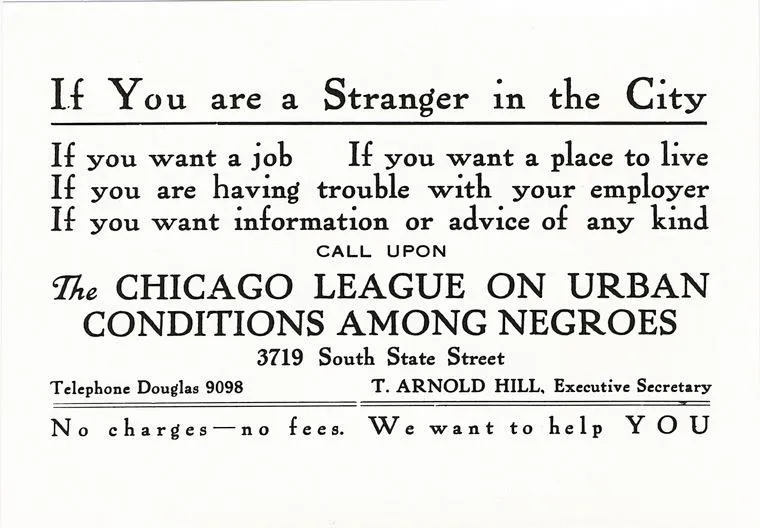

The door of escape opened during Globe War I, when slowing immigration from Europe created a labor shortage in the North. To fill the assembly lines, companies began recruiting black Southerners to work the steel mills, railroads and factories. Resistance in the Southward to the loss of its cheap blackness labor meant that recruiters oftentimes had to human action in secret or confront fines and imprisonment. In Macon, Georgia, for instance, a recruiter'due south license required a $25,000 fee plus the unlikely recommendations of 25 local businessmen, 10 ministers and ten manufacturers. Simply word soon spread amongst black Southerners that the North had opened upwardly, and people began devising means to go out on their own.

Southern authorities then tried to go along African-Americans from leaving by arresting them at the railroad platforms on grounds of "vagrancy" or tearing up their tickets in scenes that presaged tragically thwarted escapes from behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold State of war. And withal they left.

On 1 of the early trains out of the South was a sharecropper named Mallie Robinson, whose husband had left her to care for their young family nether the rule of a harsh plantation owner in Cairo, Georgia. In 1920, she gathered up her five children, including a baby withal in diapers, and, with her sister and brother-in-law and their children and three friends, boarded a Jim Crow train, and another, and another, and didn't get off until they reached California.

They settled in Pasadena. When the family unit moved into an all-white neighborhood, a cross was burned on their front lawn. But here Mallie'southward children would go to integrated schools for the full year instead of segregated classrooms in between laborious hours chopping and picking cotton. The youngest, the ane she had carried in her arms on the train out of Georgia, was named Jackie, who would go on to earn 4 letters in athletics in a single year at UCLA. Later, in 1947, he became the commencement African-American to play Major League Baseball game.

Had Mallie not persevered in the face of hostility, raising a family of vi alone in the new world she had traveled to, we might non have e'er known his name. "My female parent never lost her sophistication," Jackie Robinson one time recalled. "As I grew older, I oft thought about the courage information technology took for my mother to break abroad from the South."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12/ba/12ba7fd7-b0a4-4a57-884f-475ebc4db34c/sep2016_c04_migration.jpg)

Mallie was extraordinary in another mode. Nigh people, when they left the Southward, followed iii main tributaries: the first was up the East Coast from Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas and Virginia to Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York and Boston; the second, up the land's central spine, from Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee and Arkansas to St. Louis, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit and the unabridged Midwest; the 3rd, from Louisiana and Texas to California and the Western states. But Mallie took ane of the farthest routes in the continental U.Due south. to get to freedom, a w journey of more than 2,200 miles.

The trains that spirited the people away, and set up the class for those who would come by bus or motorcar or foot, caused names and legends of their own. Perhaps the virtually historic were those that rumbled along the Illinois Central Railroad, for which Abraham Lincoln had worked every bit a lawyer earlier his election to the White Firm, and from which Pullman porters distributed copies of theChicago Defender in hugger-mugger to black Southerners hungry for information most the North. The Illinois Central was the master road for those fleeing Mississippi for Chicago, people like Muddy Waters, the blues legend who fabricated the journey in 1943 and whose music helped define the genre and pave the way for rock 'north' scroll, and Richard Wright, a sharecropper'due south son from Natchez, Mississippi, who got on a railroad train in 1927 at the age of 19 to feel what he chosen "the warmth of other suns."

In Chicago, Wright worked washing dishes and sweeping streets before landing a job at the postal service office and pursuing his dream every bit a writer. He began to visit the library: a right and pleasance that would have been unthinkable in his home state of Mississippi. In 1940, having fabricated it to New York, he publishedNative Son to national acclamation, and, through this and other works, became a kind of poet laureate of the Great Migration. He seemed never to have forgotten the heartbreak of leaving his homeland and the backbone he mustered to step into the unknown. "We look up at the high Southern sky," Wright wrote in12 1000000 Blackness Voices. "We browse the kind, black faces we have looked upon since we start saw the light of day, and, though pain is in our hearts, we are leaving."

Zora Neale Hurston arrived in the North along the East Coast stream from Florida, although, as was her way, she bankrupt convention in how she got there. She had grown up as the willful younger daughter of an exacting preacher and his long-suffering wife in the all-black boondocks of Eatonville. After her female parent died, when she was thirteen, Hurston bounced betwixt siblings and neighbors until she was hired as a maid with a traveling theater troupe that got her due north, dropping her off in Baltimore in 1917. From in that location, she made her way to Howard University in Washington, where she got her first story published in the literary magazineStyluswhile working odd jobs every bit a waitress, maid and manicurist.

She connected on to New York in 1925 with $1.l to her proper noun. She would become the first blackness educatee known to graduate from Barnard College. At that place, she majored in English and studied anthropology, but was barred from living in the dormitories. She never complained. In her landmark 1928 essay "How Information technology Feels to Be Colored Me," she mocked the applesauce: "Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me aroused," she wrote. "It just astonishes me. How tin can any deny themselves the pleasance of my company? It's beyond me."

She arrived in New York when the Harlem Renaissance, an artistic and cultural flowering in the early years of the Dandy Migration, was in full flower. The influx to the New York region would extend well beyond the Harlem Renaissance and draw the parents or grandparents of, among then many others, Denzel Washington (Virginia and Georgia), Ella Fitzgerald (Newport News, Virginia), the artist Romare Bearden (Charlotte, N Carolina), Whitney Houston (Blakeley, Georgia), the rapper Tupac Shakur (Lumberton, N Carolina), Sarah Vaughan (Virginia) and Althea Gibson (Clarendon County, South Carolina), the tennis champion who, in 1957, became the start black player to win at Wimbledon.

From Aiken, Southward Carolina, and Bladenboro, North Carolina, the migration drew the parents of Diahann Carroll, who would become the first black adult female to win a Tony Honor for best extra and, in 1968, to star in her ain boob tube evidence in a role other than a domestic. It was in New York that the mother of Jacob Lawrence settled after a winding journey from Virginia to Atlantic City to Philadelphia and so on to Harlem. In one case there, to continue teenage Jacob safe from the streets, she enrolled her eldest son in an later-schoolhouse arts program that would set the course of his life.

Lawrence would go on to create "The Migration Series"—lx painted panels, brightly colored like the throw rugs his mother kept in their tenement apartment. The paintings would become not but the best-known images of the Slap-up Migration simply among the almost recognizable images of African-Americans in the 20th century.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/4a/5b4a1d92-ddf6-40a5-adac-040af2eaea8b/sep2016_c03_migration.jpg)

**********

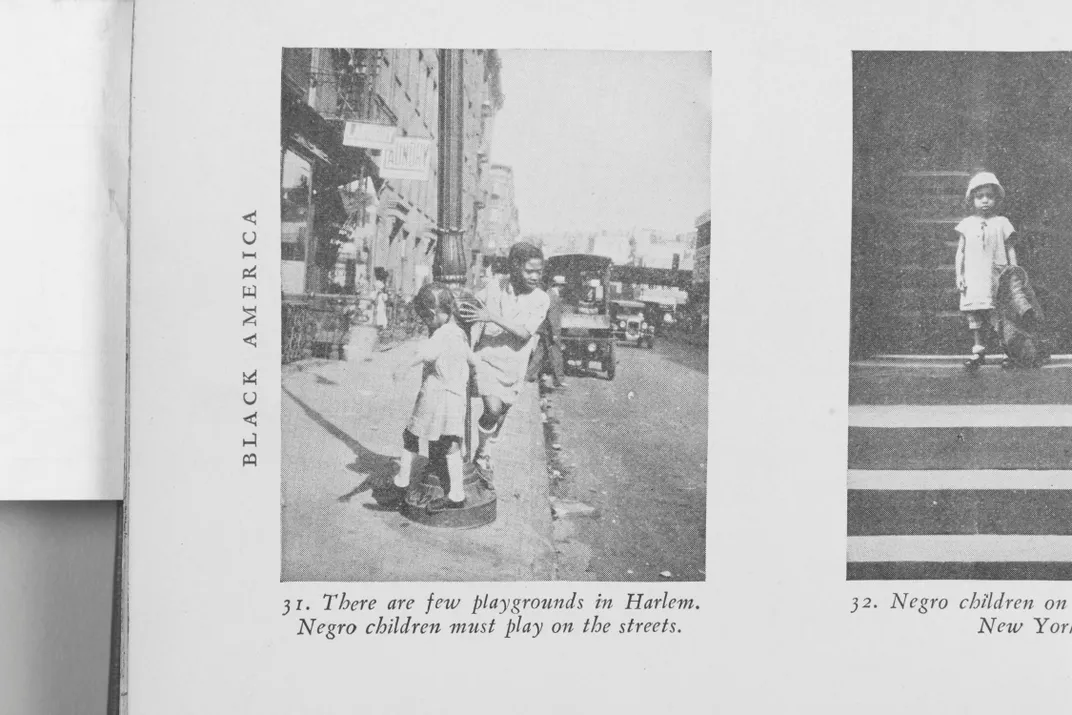

Even so throughout the migration, wherever black Southerners went, the hostility and hierarchies that fed the Southern caste organisation seemed to carry over into the receiving stations in the New Earth, as the cities of the North and West erected barriers to black mobility. There were "sundown towns" throughout the state that banned African-Americans after dark. The constitution of Oregon explicitly prohibited black people from entering the state until 1926; whites-just signs could all the same be seen in store windows into the 1950s.

Even in the places where they were permitted, blacks were relegated to the everyman-paying, most unsafe jobs, barred from many unions and, at some companies, hired only as strike breakers, which served to further divide black workers from white. They were bars to the near dilapidated housing in the least desirable sections of the cities to which they fled. In densely populated destinations like Pittsburgh and Harlem, housing was so deficient that some black workers had to share the same single bed in shifts.

When African-Americans sought to move their families to more favorable weather condition, they faced a hardening structure of policies and community designed to maintain racial exclusion. Restrictive covenants, introduced as a response to the influx of black people during the Corking Migration, were clauses written into deeds that outlawed African-Americans from buying, leasing or living in properties in white neighborhoods, with the exception, often explicitly spelled out, of servants. By the 1920s, the widespread use of restrictive covenants kept every bit much equally 85 percentage of Chicago off-limits to African-Americans.

At the same time, redlining—the federal housing policy of refusing to approve or guarantee mortgages in areas where black people lived—served to deny them admission to mortgages in their own neighborhoods. These policies became the pillars of a residential caste system in the North that calcified segregation and wealth inequality over generations, denying African-Americans the take chances accorded other Americans to meliorate their lot.

In the 1930s, a blackness couple in Chicago named Carl and Nannie Hansberry decided to fight these restrictions to make a better life for themselves and their four young children. They had migrated north during Globe War I, Carl from Mississippi and Nannie from Tennessee. He was a real estate broker, she was a schoolteacher, and they had managed to save upwards enough to buy a home.

They found a brick iii-apartment with bay windows in the all-white neighborhood of Woodlawn. Although other black families moving into white neighborhoods had endured firebombings and mob violence, Carl wanted more space for his family and bought the house in clandestine with the help of progressive white existent manor agents he knew. He moved the family late in the spring of 1937. The couple's youngest daughter, Lorraine, was seven years old when they kickoff moved, and she after described the vitriol and violence her family met in what she called a "hellishly hostile 'white neighborhood' in which literally howling mobs surrounded our house." At one point a mob descended on the abode to throw bricks and broken physical, narrowly missing her caput.

But non content but to terrorize the Hansberrys, neighbors so filed a lawsuit, forcing the family unit to move out, backed by state courts and restrictive covenants. The Hansberrys took the case to the Supreme Courtroom to claiming the restrictive covenants and to return to the business firm they bought. The case culminated in a 1940 Supreme Courtroom determination that was one of a series of cases that together helped strike a accident against segregation. But the hostility connected.

Lorraine Hansberry later recalled existence "spat at, cursed and pummeled in the daily trek to and from school. And I also remember my desperate and mettlesome mother, patrolling our household all night with a loaded German Luger, doggedly guarding her four children, while my father fought the respectable office of the battle in the Washington courtroom."

In 1959, Hansberry's playA Raisin in the Sunday, near a black family on Chicago's South Side living in battered housing with few better options and at odds over what to do after the death of the patriarch, became the first play written by an African-American woman to be performed on Broadway. The fight by those who migrated and those who marched eventually led to the Off-white Housing Act of 1968, which fabricated such discriminatory practices illegal. Carl Hansberry did not alive to come across it. He died in 1946 at age fifty while in United mexican states City, where, disillusioned with the slow speed of progress in America, he was working on plans to move his family to Mexico.

**********

The Neat Migration laid bare tensions in the North and West that were not equally far removed from the South as the people who migrated might have hoped. Martin Luther King Jr., who went northward to study in Boston, where he met his wife, Coretta Scott, experienced the depth of Northern resistance to blackness progress when he was campaigning for fair housing in Chicago decades afterward the Hansberrys' fight. He was leading a march in Marquette Park, in 1966, amid fuming crowds. I placard said: "King would look good with a knife in his dorsum." A protester hurled a rock that hit him in the head. Shaken, he fell to one articulatio genus. "I accept seen many demonstrations in the South," he told reporters. "Merely I have never seen anything so hostile and then hateful as I've seen here today."

Out of such turmoil arose a political consciousness in a people who had been excluded from civic life for near of their history. The disaffected children of the Great Migration grew more outspoken about the worsening conditions in their places of refuge. Among them was Malcolm 10, born Malcolm Little in 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska, to a lay minister who had journeyed n from Georgia, and a mother built-in in Grenada. Malcolm was 6 years erstwhile when his male parent, who was under continuous attack past white supremacists for his role fighting for ceremonious rights in the North, died a tearing, mysterious death that plunged the family into poverty and dislocation.

Despite the upheaval, Malcolm was accomplished in his predominantly white school, only when he shared his dream of becoming a lawyer, a teacher told him that the law was "no realistic goal for a northward-----." He dropped out soon afterward.

He would continue to become known as Detroit Blood-red, Malcolm Ten and el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, a journey from militancy to humanitarianism, a voice of the dispossessed and a counterweight to Martin Luther Male monarch Jr. during the civil rights movement.

At effectually the same time, a radical movement was brewing on the West Declension. Huey Newton was the impatient son of a preacher and itinerant laborer who left Louisiana with his family for Oakland, later on his father was almost lynched for talking back to a white overseer. Huey was a toddler when they arrived in California. There, he struggled in schools sick-equipped to handle the influx of newcomers from the S. He was pulled to the streets and into juvenile offense. It was only after high schoolhouse that he truly learned to read, but he would become on to earn a PhD.

In college he read Malcolm 10 and met classmate Bobby Seale, with whom, in 1966, he founded the Black Panther Party, built on the ideas of political activity offset laid out by Stokely Carmichael. The Panthers espoused self-decision, quality housing, wellness care and total employment for African-Americans. They ran schools and fed the poor. Simply they would become known for their steadfast and militant conventionalities in the right of African-Americans to defend themselves when nether attack, as had been their lot for generations in the Jim Crow South and was increasingly in the North and West.

Perhaps few participants of the Great Migration had as deep an impact on activism and social justice without earning the commensurate recognition for her function as Ella Baker. She was born in 1903 in Norfolk, Virginia, to devout and aggressive parents and grew up in North Carolina. After graduating from Shaw University, in Raleigh, she left for New York in 1927. There she worked every bit a waitress, factory worker and editorial banana before becoming active in the NAACP, where she eventually rose to national director.

Baker became the quiet shepherd of the civil rights movement, working aslope Martin Luther King Jr., Thurgood Marshall and West.Eastward.B. DuBois. She mentored the likes of Stokely Carmichael and Rosa Parks and helped to create the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—the network of college students who risked their lives to integrate buses and register blacks to vote in the most dangerous parts of the Southward. She helped guide almost every major event in the civil rights era, from the Montgomery bus boycott to the march in Selma to the Freedom Rides and the student sit-ins of the 1960s.

Bakery was among those who suggested to King, and so however in his 20s, that he accept the motion beyond Alabama after the success of the bus boycott and press for racial equality throughout the Due south. She had a bully understanding that a motion would demand Southern origins in social club for participants not to exist dismissed as "Northern agitators." King was at showtime reluctant to push his followers in the aftermath of the taxing 381-day cold-shoulder, but she believed that momentum was crucial. The modern ceremonious rights movement had begun.

Baker devoted her life to working at the ground level in the South to organize the nonviolent demonstrations that helped modify the region she had left only not forsaken. She directed students and sharecroppers, ministers and intellectuals, but never lost a fervent belief in the ability of ordinary people to change their destiny. "Requite light," she one time said, "and people volition discover the manner."

**********

Over time, as the people of the Neat Migration embedded themselves in their cities, they aspired to leading roles in civic life. It could not accept been imagined in the migration's early decades that the first blackness mayors of most major cities in the North and West would not be longtime Northerners, every bit might accept been expected, but rather children of the Bang-up Migration, some having worked the Southern fields themselves.

The man who would become the first black mayor of Los Angeles, Tom Bradley, was born on a cotton plantation in Calvert, Texas, to sharecroppers Crenner and Lee Thomas Bradley. The family migrated to Los Angeles when he was 7 years quondam. Once in that location his begetter abandoned the family, and his mother supported him and his iv siblings working equally a maid. Bradley grew upwards on Primal Avenue among the growing colony of black arrivals from the S. He became a runway star at UCLA and later on joined the Los Angeles police force, rising to lieutenant, the highest rank allowed African-Americans in the 1950s.

Seeing limits on his advocacy, he went to law school at night, won a seat on the city council, and was elected mayor in 1973, serving five consecutive terms.

His name would become a part of the political dictionary later he ran for governor of California in 1982. Polls had overestimated support for him due to what was believed to exist the reluctance of white voters to be truthful with pollsters about their intention to vote for his white opponent, George Deukmejian. To this day, in an election involving a non-white candidate, the discrepancy between polling numbers and final outcomes due to the misleading poll responses of white voters is known as the "Bradley Effect." In the 1982 ballot that Bradley had been favored to win, he lost past a single pct point.

Still, he would depict Los Angeles, the identify that drew his family out of Texas, as "the metropolis of hope and opportunity." He said, "I am a living example of that."

**********

The story of African-Americans on this soil cannot be told without the Great Migration. For many of them, the 20th century was largely an era of migrating and marching until freedom, by law and in their hearts, was won. Its mission over, the migration concluded in the 1970s, when the South had sufficiently changed so that African-Americans were no longer under pressure level to get out and were free to live anywhere they chose. From that time, to the electric current day, a new narrative took agree in popular idea that has seized primarily on geographical demography information, gathered every ten years, showing that since 1975 the Due south has witnessed a net increment of African-Americans, many drawn (like other Americans) to job opportunities and a lower cost of living, but also to the telephone call of their ancestral homeland, enacting what has come to exist chosen a "reverse migration."

The phrase and phenomenon have captured the attention of demographers and journalists alike who revisit the trend after each new census. One report went and so far as to describe it as "an evacuation" from the Northern cities by African-Americans back to the place their forebears had fled. But the demographics are more complex than the narrative often portrayed. While hundreds of thousands of African-Americans take left Northern cities, they accept not made a trail to the farms and hamlets where their ancestors may have picked cotton but to the biggest cities of the South—Atlanta, Houston, Dallas—which are now more cosmopolitan and thus more like their Northern counterparts. Many others have non headed South at all but have fanned out to suburbs or smaller cities in the North and West, places similar Las Vegas, Columbus, Ohio, or even Ferguson, Missouri. Indeed, in the 40 years since the migration ended, the proportion of the South that is African-American has remained unchanged at virtually 20 pct—far from the seismic impact of the Great Migration. And so "reverse migration" seems non only an overstatement simply misleading, as if relocating to an employer'southward Houston office were equivalent to running for 1's life on the Illinois Cardinal.

Richard Wright relocated several times in his quest for other suns, fleeing Mississippi for Memphis and Memphis for Chicago and Chicago for New York, where, living in Greenwich Village, barbers refused to serve him and some restaurants refused to seat him. In 1946, most the superlative of the Great Migration, he came to the disheartening recognition that, wherever he went, he faced hostility. So he went to France. Similarly, African-Americans today must navigate the social fault lines exposed by the Smashing Migration and the state'south reactions to information technology: white flight, police brutality, systemic ills flowing from government policy restricting fair access to safe housing and skillful schools. In recent years, the North, which never had to confront its own injustices, has moved toward a crisis that seems to have reached a boiling point in our current day: a itemize of videotaped assaults and killings of unarmed black people, from Rodney Rex in Los Angeles in 1991, Eric Garner in New York in 2014, Philando Castile exterior St. Paul, Minnesota, this summer, and beyond.

Thus the eternal question is: Where tin can African-Americans get? It is the aforementioned question their ancestors asked and answered, but to discover upon arriving that the racial caste arrangement was not Southern but American.

And then information technology was in these places of refuge that Black Lives Thing arose, a largely Northern- and Western-born protestation movement against persistent racial discrimination in many forms. It is organic and leaderless similar the Great Migration itself, begetting witness to attacks on African-Americans in the unfinished quest for equality. The natural next stride in this journey has turned out to exist non simply moving to another state or geographic region but moving fully into the mainstream of American life, to exist seen in i's full humanity, to be able to breathe free wherever one lives in America.

From this perspective, the Great Migration has no contemporary geographic equivalent because it was not solely about geography. It was about agency for a people who had been denied information technology, who had geography every bit the just tool at their disposal. It was an expression of faith, despite the terrors they had survived, that the land whose wealth had been created by their ancestors' unpaid labor might do correct by them.

We can no more reverse the Smashing Migration than unsee a painting by Jacob Lawrence, unhear Prince or Coltrane, eraseThe Pianoforte Lesson, remove Mae Jemison from her spacesuit in science textbooks, deleteDearest. In a short span of time—in some cases, over the course of a unmarried generation—the people of the Great Migration proved the worldview of the enslavers a lie, that the people who were forced into the field and whipped for learning to read could practice far more than than pick cotton, scrub floors. Perhaps, deep downwards, the enslavers always knew that. Perhaps that is 1 reason they worked so hard at such a brutal system of subjugation. The Great Migration was thus a Declaration of Independence. It moved those who had long been invisible not only out of the South but into the calorie-free. And a tornado triggered past the wings of a sea gull can never be unwound.

The Warmth of Other Suns: The Ballsy Story of America'south Swell Migration

Post a Comment for "What Percentage of Children Actually End Up Pursuing Sthe Performing Arts in Arkansas"